Raising colony rabbits for meat has been one of the most rewarding and joyful experiences on our homestead. In this article, I’ll share every step we take in the process, from breeding to dispatching the grow-outs, so you’ll have a clear understanding of what it takes to fill your freezer with nutritious rabbit meat.

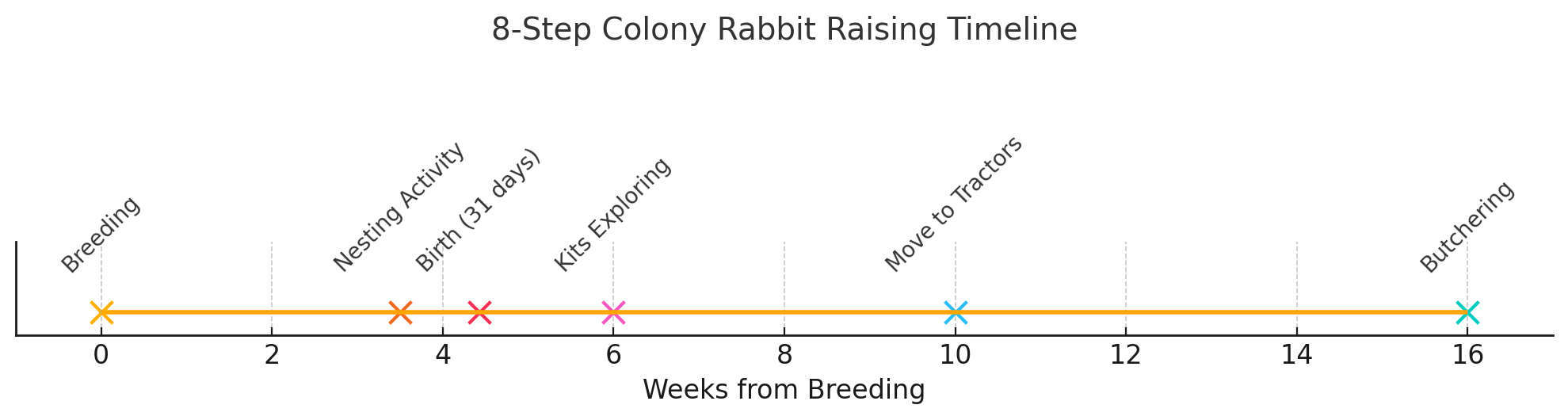

Before we get into the details, here’s a top-level overview of the process:

- Our bucks and does used to live together and were free to breed at their leisure, but we’ve decided to keep them separate going forward (for reasons I’ll explain later).

- We keep an eye on nesting activity, noting when the doe starts pulling fur and drags hay underground (which is an indication of imminent birth).

- The does gives birth (usually in underground burrows).

- We get to see the new litter when the kits start exploring the hutches (at around 2-3 weeks of age).

- I document the new litter in our rabbit tracker spreadsheet. (Here’s a duplicate version you can make a copy of for your own use.)

- When the kits are 10 weeks old, we move the male and female grow-outs out of the hutch and into separate, mobile rabbit tractors.

- Once the grow-outs have reached their butcher weight (about 5.5 pounds) at around 4 months of age, we dispatch them via cervical dislocation.

- Before the next litter moves into the rabbit tractors, we clean the equipment and make any necessary repairs.

In addition to the steps mentioned above, raising rabbits involves twice-daily chores (morning and evening) that usually take no longer than a few minutes, including:

- Refilling pellet and hay feeders (we use Canadian Timothy grass for our rabbits because it’s nutritious and palatable for rabbits).

- Checking the water nipples (we have all the nipples of our hutches attached to our filtered house water supply).

- Observing their behavior to spot any sick or injured rabbits.

We also move our mobile rabbit tractors once or twice a day (depending on how many rabbits they contain) to manage soil disturbance.

In other words, we want the rabbits to “mow” our lawn without disturbing the grass and soil so much that it would take weeks for the lawn to recover.

Due to mobility reasons, we use 5-gallon water buckets for our tractors, which we check and refill as needed.

Infrastructure We Use

As you have probably realized by now, we raise our New Zealand rabbits in colonies rather than in cages because we believe it’s a more natural approach that improves the quality of life of our animals and yields better, more nutritious meat.

As of this writing, we have several hutches of different sizes, each filled with approximately three feet of dirt and topped with pine shavings as bedding.

The deep soil enables our rabbits to burrow and dig tunnels. Not only is this a natural rabbit behavior, but it also helps the animals control their body temperature better (they disappear into the tunnels if they’re too hot or too cold).

Additionally, it virtually eliminates sore hocks and similar injuries originating from hard surfaces, such as metal mesh wire.

Of course, there are also downsides to raising rabbits in a colony, as I explain in this article.

Water and Feed

To provide feed and fresh water to our rabbits, we use a combination of Fine-X pellet feeders, 2×3-inch mesh wire to hold hay, and brass rabbit nipples attached to our main house supply via a pressure reducer and silicone line.

The advantage of hooking into our main water line (which is equipped with a whole-house filtration system) is that the water is free of chlorine, fluoride and other contaminants, and we don’t have to clean and refill buckets. That reduces chore time in the morning and evening.

We feed our rabbits “free choice” using a combination of organic pellets purchased by the pallet from New Country Organics and Canadian Timothy hay bought from a local feed store. (You can also get it online here.)

Additionally, we seasonally offer our rabbits greens from our garden and backyard, such as chicory, clover and plantain, as well as twigs and leaves from local trees (e.g., mulberry, apple or pear), or branches that may have broken off during a storm. Of course, we always check before feeding them new plants using apps like PictureThis or ChatGPT to ensure they’re not toxic to rabbits.

For example, certain leafy greens, such as kale and spinach, are high in oxalates that can cause kidney damage when consumed in larger amounts.

As a special treat — and to help protect against gastrointestinal parasites — we also offer our rabbits small amounts of pumpkin seeds that we feed to them by hand.

The benefit of feeding them by hand is that it makes them feel more comfortable when we have to handle them – which is particularly helpful for the kits when it comes to moving them to the tractor.

Breeding Strategies

We’ve been raising bucks and does in the same hutches for years. In other words, a buck would permanently stay with one or two does instead of living in a separate enclosure.

While that has been working reasonably well for us over the years, we’ve realized that it complicates breeding management.

Specifically, it makes it challenging to track their breeding performance, as we never know when mating occurred or whether a doe is pregnant or already has a litter underground.

That’s why we’ve decided to keep our bucks in separate enclosures (our two stud muffins currently reside in a mobile rabbit tractor, separated by mesh wire). When we want to breed a doe, we bring the buck to her hutch and watch them mate. If we think the mating was successful, we remove the buck and add a reminder to watch out for a new litter in the next 30-45 days.

(A rabbit’s gestation period is around 31 days, but it may take about two weeks for babies to leave the nest and surface.)

If we have reason to believe that the mating wasn’t successful (e.g., we didn’t see the classic “falling off”), we try again the next day.

What’s falling off? When a buck finishes mating, he’s still angled forward with his hind legs raised, and the instant he dismounts there’s nothing to stop him from tipping over — think of it like stepping off a skateboard without bending your knees. His front feet hit the ground first, his back end swings up, and he often slides or flips sideways because his center of gravity shifts so abruptly. Rabbits also lack the strong pelvic bracing you see in larger mammals, and most homestead surfaces (grass, dirt, and even wire flooring) don’t give enough grip for a slick, controlled hop-off. So from the outside it looks like he literally “falls off” the doe every time, though it’s just basic physics and rabbit anatomy at play.

Kit Care (0-10 Weeks)

During the first few weeks of the kits’ lives, we try to handle them as much as possible (without stressing them out) so they get used to us. That makes handling them as they get older easier.

Rabbits that haven’t been handled when they were young tend to be shyer and more challenging to catch when the time comes to move them to the mobile rabbit tractors.

Our rabbits stay with their mother for at least 10 weeks to ensure they’re fully weaned and can live off pellets, grass and hay. If we don’t have any available tractors, they may stay a few weeks longer with their mom and the hutch.

During the first few days and weeks of the bunnies’ lives, we watch for health issues, including “the sniffles,” which is a respiratory infection that causes mucus to discharge from the nose (as well as sneezing), and which can lead to death. There isn’t much we can do to treat the infection, but if it becomes too severe and the rabbit suffers, we dispatch it.

Selective breeding and culling are the most effective methods for raising resilient animals that are resistant to disease. We had quite a few cases of the sniffles at the beginning of our rabbit journey, but we managed to get to a point where severe cases are few and far between.

We’ve also had two baby rabbits over the years that had a broken hind leg. I shot one, and the second one (which appeared to be doing quite well despite its handicap) disappeared from the hutch, never to be seen again.

Rotational Grazing With Mobile Tractors

Once the young rabbits have been fully weaned, we move them to mobile rabbit tractors we built based on Joel Salatin’s plans (see the video above for more details).

The advantage of moving them out of the hutches is that it frees up space for the next litter, reduces the manure load, and lowers feed costs. We can accomplish the latter by giving the grow-outs in the rabbit tractors access to fresh pasture.

Another benefit of implementing a rotational grazing system is that the rabbits fertilize the pasture with their manure, which, in contrast to chicken manure, doesn’t have to be composted beforehand.

One critical thing we’ve learned is to separate the males from the females before moving them into the tractors, to prevent early-maturing bunnies from mating in the tractors before being dispatched.

We had one doe give birth in the tractor, and we accidentally dispatched two does that were pregnant. Needless to say, I felt terrible that our mistake cost a bunch of unborn bunnies their lives.

Butchering and Processing

Once the rabbits have reached their target butchering weight (for us, that’s around 5.5 pounds), we dispatch them.

Our preferred dispatch method is cervical dislocation because it’s fast and relatively foolproof. Once the rabbit has been dispatched, we sever the major blood vessels around the trachea to bleed the carcass, which improves the taste of the meat.

After skinning and eviscerating the rabbit, we rinse the carcass with water and place it in a cooler filled with ice water to cool it down. I always inspect the liver, heart and lungs to confirm the animal is healthy. If everything checks out, we save the organs – including the liver, heart, kidneys, spleen, lungs and stomach – to feed to our German Shepherd.

Once all the rabbits have been dispatched, cleaned and cooled, we cut them into smaller pieces and store them in vacuum freezer bags for our consumption.

Rinse (Literally) and Repeat

Before we reuse the mobile tractors, we hose them down, clean the feeders and water buckets, and make any necessary repairs.

Rabbits love chewing on stuff to keep their teeth trimmed. As a result, we have to replace parts of the tractor that they chewed through.

That’s why it’s important to avoid using lumber that is toxic to rabbits (such as cedar) in places they’re likely to chew on (like the crossbars on the inside that add stability to the structure).

Once the tractors have been cleaned and any necessary repairs have been made, we move on to the next batch of grow-outs and start the process all over again.

How Our Process is Different from Conventional Rabbitries

Our colony and pasture-based setup is significantly different (and perhaps more involved) than that of conventional rabbitries, where animals are raised in small cages.

However, we chose a colony and pasture-based approach for the same reasons we raise our chickens on open pastures: it’s better for the animals, better for the soil, and better for the quality of the final product (the meat).

We firmly believe in raising animals in a way that allows them to pursue their natural behaviors. Chickens like to roam, scratch, roost, and dust bathe, and they need insects, grasses, water and sunshine for optimal health. You can’t meet most of the needs of chickens if you raise them in cages or chicken houses.

Similarly, rabbits (except for hares or certain breeds, such as the American Cottontail) enjoy living in colonies, where they burrow and build underground nests. Rabbits raised solitary in cages can’t express any of those behaviors.

Does our process make raising rabbits for meat in a commercial setting significantly more difficult? Definitely, but I’d argue that if you cannot commercially raise animals in a species-appropriate setting, perhaps it shouldn’t be done.

Final Thoughts

The reason we decided to raise rabbits for meat is that our current homestead isn’t big enough to raise ruminants (like cattle), and because rabbits are a joy to raise. They’re easy to handle, they’re not noisy, they produce tons of fertilizer in the form of manure, and they’re cute (especially the babies).

As we prepare to move to a new 45-acre lot to establish our new homestead and introduce ruminants – including cows, sheep and goats – we’ll most likely reintroduce rabbits, keeping a breeding duo because they’re so much fun to raise. But we won’t depend on them for meat.

Ruminants can be raised without the need for hutches or cages, and without having to buy pellets. All we need is grass, rain and sunshine – all of which we’ll have in abundance on the new property.

Now I’d like to hear from you! Have you considered raising rabbits for meat or fur, or are you already doing so? What’s your process look like? Let us know by leaving a comment below.

Michael Kummer is a healthy living enthusiast, the founder of MK Supplements and the host of the Primal Shift podcast. His goal is to help people achieve optimal health by bridging the gap between ancestral living and the demands of modern society. He runs the Kummer Homestead with his wife Kathy and their two children.